| Michael W. Hunkapiller |

|

|

|

|

|

|

[figure 39]

[figure 40]

[figure 41]

[figure 42]

[figure 43]

[figure 44]

[figure 45]

[figure 46]

[figure 47]

[figure 48] |

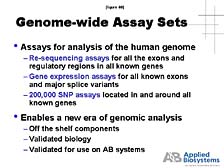

One of the

commercial initiatives that the partnership between Applied Biosystems,

Celera Genomics, and our newly created joint venture, Celera Diagnostics,

has added is an initiative to look at diversity across the human

genome. [figure 39] The key, here, is to be able to re-sequence

all of the gene areas within the chromosomes and create assays that

allow individual researchers to study whichever portion of the genome

they want. [figure 40] For example, to look at the variation of

cells within that sequence, to look at the expression of those individual

genes in a robust way, and to be able to look at all the sites of

diversity, it is useful for researchers to not have to start that

process to create their own assays, but to have ones that are already

validated by a commercial company.

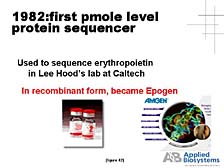

The final area I will touch on is proteomics, an area which I know

has a great deal of importance in some of the strategic, long-term

research plans within Japan, as elsewhere in the world. [figure

41] In this respect, Applied Biosystems and the tools that we developed

initially at Lee Hood's lab have played a role already. For instance,

the first small-scale protein sequencer was developed at Lee's lab

and was the first commercial product provided by Applied Biosystems

in 1982. [figure 42] This protein sequencer was used, particularly

by biotech companies, to look at key, biologically functional proteins.

The sequencer aided these companies in the process to eventually

commercialize some of the key proteins as pharmaceutical compounds.

[figure 43] The problem of looking at not just a single protein,

but the proteome-wide collection of proteins, is a daunting one.

One doesn't have a PCR tool that allows you to make unlimited quantities

of individual proteins, so you have to rely on what's there -- which

might not be very much in a lot of cases. The number of proteins

that exist and the complexity of their chemical make-up are much

greater than in the case of DNA.

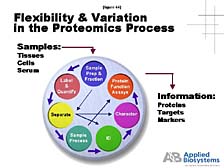

One needs to understand that it's a complicated process. It starts

with the fact that the way you prepare a particular protein for

analysis is going to be different from the way that you prepare

another one. [figure 44] Whereas, in the DNA world, it's pretty

much the same. You are also after a much more complicated set of

information in the case of proteins. Therefore, there is not likely

to be a single tool that does what DNA sequencing, or even PCR,

has done for nucleic acid studies. Instead, there are some tools

that allow you to attack specific areas of protein structure and

function problems. [figure 45] One of these that we've focused on,

and what Craig will touch on a little bit more, is mass spectrometry.

It is an old tool, from a chemical analysis perspective, and one

that's increasingly applied to protein studies. The difficulty,

here, is there are a lot of bottlenecks. It's hard to prepare a

large number of samples for analysis for very large-scale proteomic

studies. It's even more difficult to interpret the data that one

generates by analytical processes such as mass spectrometry. Thus,

the process doesn't have nearly as high a throughput as what's been

achieved for DNA analysis in the last few years.

The goal that we have now in looking at new technologies is to eliminate

those bottlenecks, so one can have a high throughput in proteomics-level

studies. This is really where functional activity occurs within

a cell. It is a challenge which has not been fully realized yet,

but one in which there is a substantial amount of effort, from our

own laboratories, and others as well.

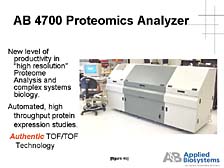

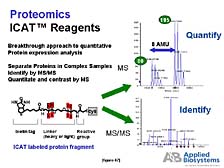

One of the tools that we have recently announced is a new generation

of mass spectrometry tools applied specifically to the proteomics

challenge. [figure 46] This tool allows you to cut down, to some

degree, on sample prep problems because they can analyze accurately

more complicated protein mixtures, and do it in a much faster rate

for components than what was possible with the earlier technology.

Therefore, we hope to present this as the first "proteomics analyzer,"

at least for structural proteomics.

That said, hard work can solve a lot of the problems, for example,

work in areas such as the chemistry required to be able to prepare

the elements of proteins that you want to study. Remember the study

of very complicated molecules is in its infancy as well. One of

the newer tools, developed by Reudi Aebersold at the University

of Washington in Seattle, is one that we have been commercializing

in order to help address some of these problems. [figure 47] This

tool allows differential isotope-labeling methodologies to look

at protein expression, which has been a particularly intractable

problem in the case of proteins for which you don't have a good,

very specific functional activity assay. While we have commercialized

this technology only recently, some of the large proteomics labs,

such as Celera and Oxford Glycosystems in the U.K., are already

reporting fairly remarkable results with its use to study protein

expression in a broad sense.

Let me end my presentation by reminding you where I started. We

are in the business of providing tools that enable the life sciences

research community to carry out the basic task of understanding

the function of biological systems. This includes finding out how

one can intervene when there are problems in the form of medical

therapies, how one can help diagnose problems, and how one can use

biology as a tool to solve a host of commercial problems, from agriculture

to the identification of criminals. [figure 48] The bottom line

is that no single discipline can solve this problem. Biology is

a complex enough endeavor that it requires the combined effort and

expertise of many disciplines to produce analytical systems that

can help unravel these problems. We are proud that we have been

a part of helping spur this process over the last twenty years or

so, and we would expect to continue to do so going forward into

the future.

With that I will turn it back over to Dr. Matsubara.

MODERATOR: Thank you very much, Dr. Hunkapiller, for a wonderful

presentation. |

|

|